Raising Boys in a Land of Small Men

Reflections on the Son of God, friendship, and The Son of Rambow

I glanced at the calendar today and realized there are only two weeks left of Lent. This one, and then, Holy Week. This year feels different. In past years of Lent, it’s really only been about what I was abstaining from. The focus was on the thing I set aside. A sort of, “shame on you” situation with my finger pointing at myself, and maybe by the end of this forty day purgation I’ll be more holy. But if holy means to be closer to God and I was only looking at myself the whole time, I’m not sure I was that much closer by the end.

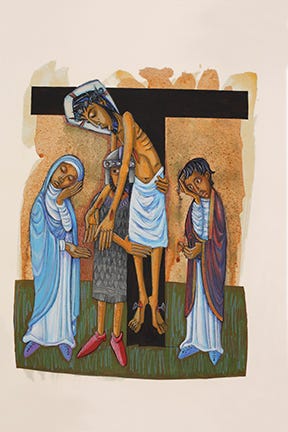

The other week my friend Allie came by. Rain had been falling sideways all day, a lot like it is as I write to you. Allie and I are part of the Lament Team at our church and we’ve been asked to help lead the Good Friday service. Seeing as that day is pretty lamentable and all. As we nestled in for the next couple of hours going over this resource for the Stations of the Cross, the journey became more and more laborious. I’ve walked The Stations of the Cross many times at our local Grotto, and prayerfully contemplated the images of

. Usually, the station where Jesus’ dead body is taken down off the cross is the one I sit at for longer than usual. While others move on, I can’t get over the ones who stayed. The ones who didn’t look away even as the One they love was despised and His eyes were, quite literally, closed in death. I’m struck by even in His death, our Lord was an obstacle to religion. According to Jewish law, they needed to take down the bodies before Sabbath. And just in case they weren’t already dead, they broke their legs. Again, even in death, Jesus winks from the abyss and, fulfilling His Word, says, “No need to break mine.”Now it was the day of Preparation, and the next day was to be a special Sabbath. Because the Jewish leaders did not want the bodies left on the crosses during the Sabbath, they asked Pilate to have the legs broken and the bodies taken down. 32 The soldiers therefore came and broke the legs of the first man who had been crucified with Jesus, and then those of the other. 33 But when they came to Jesus and found that he was already dead, they did not break his legs. 34 Instead, one of the soldiers pierced Jesus’ side with a spear, bringing a sudden flow of blood and water. 35 The man who saw it has given testimony, and his testimony is true. He knows that he tells the truth, and he testifies so that you also may believe. 36 These things happened so that the scripture would be fulfilled: “Not one of his bones will be broken,”[c] 37 and, as another scripture says, “They will look on the one they have pierced. (John 19:31-37)

To sit at this station is to ponder the heaviness of Christ’s dead body, and ask ourselves, “Am I willing to help?” Even if it’s inconvenient? Even if it’s an obstacle to the law? And maybe it’s not about will. Maybe it’s about affection. How can one be willing if there is no love?

But if I may, there are two other stations that I lingered at this time. To do this, we need to turn around and go back.

Boys growing up

I’ve had quite a few friends ask me what it’s like to be a mom of boys. Most of them are other female friends, and we laugh and cry and shake our heads about things like sitting down to go to the bathroom in the middle of the night only to sit on a seat with pee all over it. Or, the pure physicality of our boys. (Be kind, I am generalizing here). I’ve learned to let mine duke it out. Mine are first grade and third grade and still carry their own kind of sweetness with a dash of sourness and outright rage from time to time. But what’s stuck with me from these conversations was one from a friend who’s about to be a dad for the first time. When he found out that him and his wife were going to have a boy this spring, his heart was conflicted.

“I feel like it would be easier with girls,” he said. “Applaud them and listen to them, and teach them to stand up for themselves. Teach them that their voice matters.”

And then with a smirk, he said, “But with boys, you basically have to teach them how not to be a jerk.”

I laughed and replied with a solid, “yeah.”

Ben and I watched one of our favorite movies with our boys recently. Their first PG-13 movie, seared in their memories. Set in 1980’s England, Son of Rambow is about two boys who become unlikely friends while creating a remake of “Rambo: First Blood.” It’s a testament to the power of imagination, play and friendship. They both laughed hysterically when Will flew the dog into his science teacher’s window, and when Lee makes Will do all of the stunts.

Will, a boy growing up under the smothering legalism of the Plymouth Brethren and Lee, a rich kid who’s parents aren’t around and a bully for an older brother.

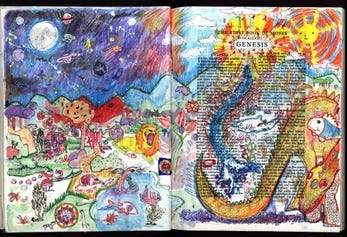

While the environment of Will consists of rigid (literally, blank) walls, his imagination is brimming with life. So much so, it spills out onto the pages of his Bible.

Meanwhile, Lee is constantly getting into trouble at their school, and notices Will’s secret inner life. When Will is waiting outside the classroom while his classmates watch something on TV (no TV for Plymouth Brethren), Lee get’s kicked out of his own class and everyone is happy for it.

One boy is dying for an escape, and the other is dying to be seen. Actually, in their own way, their both dying to be seen and known. Out of this need, forms one of my favorite on-screen boy friendships.

Larry and Sid from Wallace Stegner’s Crossing to Safety

Sam and Frodo from Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings

The Dearly Beloved by Cara Wall

Rick and Louis in Casablanca (although, this is film)

Adam Trask and Lee in East of Eden

Noe Crowe and Christy McMahon in This is Happiness

Beloved by Toni Morrison

(one reader jokingly but aptly commented that reading about male friendships is simply boring in an empirical world. Why have friendship when you can have dominion and power?) To which, Wallace Stegner would probably agree:

“How do you make a book that anyone will read out of lives as quiet as these? Where are the things that novelists seize upon and readers expect? Where is the high life, the conspicuous waste, the violence, the kinky sex, the death wish? Where are the suburban infidelities, the promiscuities, the convulsive divorces, the alcohol, the drugs, the lost weekends? Where are the hatreds, the political ambitions, the lust for power? Where are speed, noise, ugliness, everything that makes us who we are and makes us recognize ourselves in fiction?”

(Crossing to Safety)

I would venture to guess there’s a reason why Lonesome Dove, a book written in 1985, a tome of nearly 900 pages, is experiencing a renaissance. (I’ve got it sitting on my bookshelf right now, waiting for me to jump in this summer). After all, Larry McMurtry had a good teacher in Wallace Stegner. Not to mention Wendell Berry also being a student of his at Stanford. And because of the stories of Wendell Berry, I believe we’re all nudged a little closer into friendship with God.

A thread running through all of these friendships is strung with the needle of vulnerability. That big word that’s so alluring and scary. That word that requires safety, emotional regulation, humility, grit, hope, courage, playfulness, and an ability to feel pain. To suffer. A word that requires, for a man: weakness. Brene Brown's Ted Talk on Shame is hands down, one of the best descriptions of how women internalize shame versus men. At 16:40 you hear her tell this story about shame and men:

“I did not interview men for the first four years of my study. It wasn't until a man looked at me after a book signing, and said,

“I love what say about shame, I'm curious why you didn't mention men?”

And I said, "I don't study men."

He said, "That's convenient."

And I said, "Why?"

And he said, "Because you say to reach out, tell our story, be vulnerable. But you see those books you just signed for my wife and my three daughters?"

I said, "Yeah."

"They'd rather see me die on top of my white horse than watch me fall down. When we reach out and be vulnerable, we get the shit beat out of us. And don't tell me it's from the guys and the coaches and the dads. Because the women in my life are harder on me than anyone else."

Oof. That hits hard, ladies, doesn’t it? (Maybe my next essay will be on women and our eighth deadly sin - Self Contempt).

In Curt Thompson’s book, Soul of Desire, he makes the observation that to draw closer to God, to grow in intimacy with Him, is to suffer. I don’t think it means misery and deprivation. Anyone who has loved and been loved whole heartedly knows that to suffer with is an act of compassion, and therefore some small death of ourselves is required. Maybe this is the bridge that Stegner crosses. One that takes us from chaos yearning for order, and over to safety. To cross into safety is to be able to practice here on this conflicted earth for the Kingdom of God. I think that’s the painful part, because it involves telling our stories honestly and compassionately in the presence of others who won’t get up and walk out because it’s just too painful.

In other words, again in Soul of Desire, Curt Thompson summarizes Paul by noticing,

“to religious folk who are more committed to their religion than to telling their stories as truly as possible, the gospel is a stumbling block; it’s painfully confusing. And to nonreligious folk who are just as wary of telling their stories truly, the gospel is utterly foolish; it’s painfully threatening.”

For those of us who have a hard time being wrong, Jesus is always going to be a pebble in our shoe until we sit down, take our shoe off, and have a good long conversation with Him about it. Some of us might be so used to walking on rocks by now, we might not even notice. In which case, He might need a bigger stumbling block to get our attention. Either way, that pebble might just be chipped off from the stone that the builders rejected and was rolled away anyway.

And for those of us who have been equally committed to telling our stories honestly and vulnerably, even in the absence of hope, I want to say to you, I see you. I see how hard you’re working to be true to yourself. To be a person of integrity and worthy of love. I see you telling your painful stories and dying for justice. I see the complete terror in your eyes in even entertaining the idea of sitting down with Jesus. Because what if all the pain you’ve ever gone through is meaningless? What if there is no justice? What if He gaslights you and steals all those stories that are so intimately and rightly yours, and asks, Can I have them?

By now, we’re not just talking about boys and men, we’re talking about all of us.

Coming in from the country

“As they led him away they took hold of a certain Simon, a Cyrenian, who was coming in from the country; and after laying the crossing on him, they made him carry it behind Jesus.” (Luke 23:26)

At this fifth station of the cross is where I found myself lingering. Here is this man, who was “coming in from the country” into Jerusalem. I’m guessing it was to celebrate Passover since it was that time, and being a Cyrenian (currently Libya), he most likely was a Hellenistic (Greek) Jew.

Did he know who Jesus was? He must’ve. Did he believe Jesus was who He said He was? We don’t know.

He doesn’t seem to have much choice in the matter. He’s walking into town, happens upon a crucifixion, and gets told to help carry the cross of Jesus. If I happened upon such a scene, a scene that involves three men carrying crosses on their way to be crucified, I would hope I could help carry at least one. No matter who they were.

This is a hard scene to imagine in the Land of the Free and Home of the Brave. As I said earlier, it is equally confusing and terrifying. As Skye Jethani poignantly wrote in The Land of Small Men,

“What has me exhausted and saddened today is the realization that our world is not only filled with small men, but that both the church and the culture celebrate their smallness. We have become enamored with men of anger and division believing these are marks of true leadership because it has been so long since most of us have encountered anything else. What we long for, what I long for, is leadership of true gravity—men and women of undeniable mass who do not need to rely on the false manipulations of anger and rightness to affect the world.”

I know such men that do not need the stars and comets to applaud for them. Their souls carry weight, and time slows down when you’re around them. Like the sun, they know their power and so, they are humbled. Their light carries such strength because they know that it is not their own, and it is not there’s to have.

It is theirs to steward.

It angers me that there are no role models for my boys to look up to in this current administration. There is nothing to admire as they sit in their box seats of power. They know their power and abuse it.

But you know who they can look up to? Their dad. They’re coaches. Their grandpas. Their uncles. The older boys and men who play with them and listen to them and treat them not as less-than. Their teachers and pastors.

They can look up to a man who came in from the country and helped the Son of God carry His instrument of death because He couldn’t carry it himself.

Good stories and movies that bring to life all the pain of growing up, infusing our imaginations with a life that could be possible. Stories that see us in our neediness and pain, that give us a hug and say, you’re gonna be ok, kid. I see you having a hard time and there’s no shame in that.

There’s no shame in that. There’s no need for self-pity or self-condemnation, beloved. Because the Man who was so needy and couldn’t even carry His own cross, accepted help from a stranger. And even though we suffer as we grow in friendship with the Weightiest of All Souls, there are no more shadows as the Light pours out of His side, pulverizing our shame.

Again, Curt Thompson:

“Moreover, the more finely the mineral is pulverized, the greater the refraction of the light and the more expansive the beauty will be. We practice ‘preaching Christ crucified’ in our confessional communities. Not in order to check some theological box that verifies unsullied belief but to speak truly of our lives, which in all of their desires also carry great grief. This grief is then transformed by our lament in the presence of others and by the faithfulness of those who will not leave the room.”

The stories of The Son of Rambow grow up into the stories of men. And if they’re lucky, they get to learn how to be children again, like in this stunning portrayal of grace in the film Sing Sing.

They play. They confess. There’s accountability and dignity in being their whole beautiful and terrible selves. And there’s a heck of a lot of imagination. Enough to maybe even one day look back and say, that stone really did roll away in a land of small men.

As a dad to three boys, and a boy myself, can confirm. What a beautiful reflection, Janell. I've got to watch Son of Rambow now!

Such a good read Janell. You always make me think and smile and tear up and just wanna curl up in a lonely and cozy corner and keep reading. You are gifted. Always love your recommendations. Haven’t seen Sing Sing yet but love Son of Rambo.